3. Triumph and Controversy

| Key Dates # |

|

|---|

| 312 | Constantine victorious over Maxentius at the battle of Milvian Bridge, near Rome;

becomes Emperor of the West

|

| 313 | Edict of Milan provides religious tolerance and gives Christians equal rights as

followers of other religions

|

| 316 | Constantine outlaws and banishes the Donatists

|

| 314 | Constantine proclaimed Emperor of East and West - favours Christianity

|

| 325 | Council of Nicaea condemns Arianism

|

| 328 | Athanasius becomes Bishop of Alexandria

|

| 345 | John Chrysostom, a reforming teacher, is born

|

| 347 | Jerome, Bible scholar and author of the Vulgate, is born

|

| 361-363 | Reign of Julian the Apostate; restores paganism, opposes the power of the Bishops

|

| 367 | Canon of 66 Books in the Bible is officially accepted (re-affirmed in 382, 393, 397)

|

| 379-395 | Reign of Theodosius, established Christianity as the official religion of the empire

|

| 381 | Council of Constantinople, concerned with the nature of Jesus Christ; coincided

with edict by Emperor Theodosius that all subjects were to believe in the Trinity

|

| 386 | Conversion of Augustine of Hippo

|

| 389 | Birth of Patrick, missionary to Ireland (died 461)

|

| 400 | Death of Nestorius

|

| 410 | Fall of Rome to Alaric and the Visigoths

|

| 413-416 | Augustine writes The City of God, a response to accusations Christians were

responsible for the fall of Rome

|

| 431 | Council of Ephesus, also debating the divinity of Jesus Christ

|

| 451 | Council of Chalcedon, further debates about the divinity of Jesus Christ

|

| 476 | End of the Roman Empire; Romulus Augustulus is deposed by German general

Odoacer.

|

Overview

One of the ironies of Christian history is that great persecutions often saw aggressive evangelism

and rapid growth, but as the church became officially tolerated it passed into a period of

theological confusion and diminished evangelistic effort. By the end of the 5thcentury, pagan

temples were largely neglected, whereas the church was established and powerful, yet

increasingly institutionalised. One of the trigger points was the conversion of Constantine to

Christianity in 313 AD. The 4thcentury was a period of consolidation of the church within the

political landscape and bitter debate over basic beliefs about the person of Jesus Christ.

Triumph - Constantine

Constantine's formal religion was originally the worship of the Unconquered Sun. However,

according to tradition, on the eve of a crucial battle with Maxentius (a rival, stronger contender

to the throne), Constantine asked "the Supreme God" for a sign. The response was a cross in

the sky with an inscription that can be translated, "By this sign conquer".

The story has never been satisfactorily verified, but the conversion of Constantine to Christianity

marked a turning point. Christianity became the favoured (though not yet official or exclusive)

religion of the empire and changes he initiated made it easier for Christians to expand their

influence.

Over time, Constantine aligned himself with the established church leadership. He often

became involved in issues the church was facing; he sought to settle matters confronting the

bishops; this was the first time a head of state was personally involved in church affairs and

marks the beginning of political interference in the Kingdom of God, the Christian community.

The descendants of Constantine (with a single exception, Julian the Apostate, one of his

grandsons, who attempted to re-assert the traditional pagan religions) were also nominal

Christians. In the space of a century Christianity went from being a religion under fire to the

predominant faith of the Empire, with the state influential in how it operated.

Controversies

Early controversies in the church centred on:

- the universality of the message (not a sect of Judaism)

- how to understanding and interpret the Bible (the Jewish OT, in the absence of the NT

- the nature of Christ; how to explain Jesus as True God & True Man (unknown in paganism)

- the person and nature of the Holy Spirit

- the Trinity

- the ecclesiastical and civil scope and authority of church structure/leaders (not all

outcomes were positive, in particular decisions that increased clericalism in the church)

- the increasing role of the state in church life (and vice versa)

- dealing with schisms and promoting unity in the growing Christian community

- how to deal with Christians who lapsed (eg in the face of persecution) but then repented

- how to approach fundamental Christian doctrine

- agreement on doctrines and formulation of statements of faith in the context of heresies

- intersection with non-Christian philosophies and religions (Christianity was theologically

exclusive but often syncretistic in practice)

Donatists

This movement stemmed from a controversy surrounding the ability of lapsed Christian leaders,

or those who collaborated with the Roman persecutors (in particularly leaders to informed on

other Christians to the Romans), were fit persons to distribute the "sacraments". Donatus (a

Bishop of Carthage) taught that the validity of the sacraments depended on the moral character

of the minister involved, and that those who had committed apostasy (fallen away) in the face

of persecution, or betrayed follow-Christians, had disqualified themselves from ministry.

The Donatists set about rebaptising church members who had been baptised by ministers

accused of collaboration. The central church hierarchy opposed this because it took the matter

out of their hands, especially when consecrated bishops were not recognised as such and

Donatists only accepted the spiritual authority of members of the sect whose moral authority

had been judged (by them) to be satisfactory. Constantine sided with the church hierarchy and

banned the group, but this only fuelled debate in many places and the movement grew.

The tide changed when Augustine spoke out against the Donatists. Theologically, the weakness

of the movement was the notion that any minister could ever be pure enough to function as

such. All Christian ministers are human and succumb to temptations. The idea that such a

person could not be an effective minister of Christ was unsustainable. Also, God's acceptance of

us is not based on the moral standing of church leadership, but our own conscience before Him,

and our dependence on the work of Christ for salvation. In essence, whether or not the

Donatists excluded individual ministers did not reduce the value of any sacrament.

In 411 the sect was again officially banned.

Arianism and the First Council of Nicaea

Divisions continued, along theological fault lines. Christianity grew up in a world with deep,

powerful cultural traditions. One of the greatest early threats came from Arianism. From

around 312 Arius (a church presbyter from Alexandria) preached a version of Christianity that

challenged the conventional view about the divinity of Christ. He taught that Christ was not

eternal, but had a beginning, that he had come into being out of non-existence; that he was a

creature made by God. He was the most noble of created beings, who went on to create the

Holy Spirit and the physical universe, but he was inferior to God, the Creator, who eventually

"adopted" Him as His Son. Christian leaders took sides for and against (mostly against) Arius.

To settle matters, Constantine called the first ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 324. Apart from

the Council of Jerusalem, this was the first event of its kind. Constantine sought to bring

together all of the major church leaders from across the empire; an estimated 1800 were

invited; around 300 participated. Bishops assembled and debated the nature of Christ, the cult

of Arianism, Easter, whether or not heretics should be baptised and what to do with lapsed

Christians who repented.

In contesting various positions about who Jesus was, what was at stake was whether He was of

the same essence as God or of similar essence as God. The Council ultimately resolved that He

was; the Son of God, pre-existent with the Father, only begotten of the Father (from eternity),

of the substance of the Father, very God of very God, ie Jesus Christ was God, eternal, revealed

in human flesh. Anything less threatened the Trinity, if Jesus is not equal to the father.

Their conclusions, more or less in this form, formed the basis for what became known as the

Nicene Creed.

Arius and his followers were banished from Rome. His works were burned. Anyone possessing

them was under threat of execution. Easter was formally separated from the Jewish Passover

feast. This was largely a reflection of the dominance of Gentiles in the church. The Council also

decreed a number of so-called canon laws, which set out to regulate church life and procedures.

Two years later Constantine welcomed Arius back. His opponents, especially Athanasius, were

then banished. The church in Europe was henceforth affected by division into pro/anti-Arian

camps.

While Christianity was not yet the official religion of the empire it was dominant. In 321 Sunday

was proclaimed a day of rest in honour of the sun.

The Nicene Creed (325 AD)

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all

things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the

Father before all worlds; God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God;

begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things

were made.

Who, for us men for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate

by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, and was made man; and was crucified also

for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; and the third day He

rose again, according to the Scriptures; and ascended into heaven, and sits on

the right hand of the Father; and He shall come again, with glory, to judge the

quick and the dead; whose kingdom shall have no end.

And I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of Life; who proceeds from

the Father [and the Son]; who with the Father and the Son together is

worshipped and glorified; who spoke by the prophets.

And I believe one holy catholic and apostolic Church. I acknowledge one baptism

for the remission of sins; and I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life

of the world to come. Amen.

(The Nicene Creed is used by the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox

Church, Church of the East, Oriental Orthodox churches, Anglican Church and

most mainstream Protestant denominations. The so-called "Apostles Creed" was

written later; the earliest reference to it is dated 390 AD.)

Many Roman Catholics believe that the Council of Nicaea recognised the role of the Bishop of

Rome as the head of the universal church. However, the Council did not do this.

Pelagianism (345-420)

Born in Britain, Pelagius was a well-known teacher in Rome. He taught that human nature is

basically good and that people could keep God's word and requirements (without the need for

grace). Pelagius taught that, just as Adam had to make a choice in Eden, the same choice is

offered to individuals, who have the capacity to decide either way (including the ability to

choose to live a perfect life); he regarded Adam's sin as an example and a warning for us. He

likewise taught that Jesus' life was an example for us to follow, however he did also believe in

the atonement.

The fundamental weakness in Pelagius' teachings is that he failed to acknowledge that all are

sinners (Ephesians 2:3; Psalm 51:5; Romans 3:23) and in need of the grace of God for salvation

and Christian living. Augustine, who believed in the doctrine of original sin and the need for

divine intervention to bring about change, opposed Pelagius.

The Council of Constantinople (381)

Theodosius (346-395) was the last emperor to rule over a united Roman Empire. In 380 AD he

established Christianity as the state religion, with the Nicene Creed as its statement of faith,

and convened the Council of Constantinople to validate this. The Council debated and reaffirmed

Christian beliefs, including the Trinity and the deity of the Holy Spirit. In January 381

Theodosius issued a proclamation mandating belief in the Trinity as a central plank in

Christianity; all other beliefs were declared to be heresies, subject to civil and divine

punishment. Paganism was banned. (Judaism also fell outside the law.) Some historians claim

that Theodosius imposed his will on the Council. If this is the case, it may have been the hand

of God at work in the context of church-state politicisation and cultural, theological debate.

The Council of Ephesus (431)

This council of Bishops was called to deal with the teachings of Nestorius, Bishop of

Constantinople, who taught that Jesus Christ had two distinct natures, to such an extent that his

detractors claimed he taught the divine and human Jesus were in fact two different persons.

Monophysites (Greek: monos = "only, single" + physis="nature") taught that Jesus had a human

nature for the purpose of the incarnation, but now had only a divine nature. Nestorius had also

opposed a theological tide that resulted in Mary being declared Theotokos, the Mother of God;

Nestorius insisted that Jesus was the mother of Jesus the Man, but not the mother of his deity.

Ultimately he was exiled.

Monophysite movements continue to function in the Syrian orthodox of Church of Antioch and

the east in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, as well as among the Copts of Egypt.

The Council also dealt with Pelagianism and excommunicated its leading proponents.

Some Influential Christians During the Fourth and Fith Centuries

Augustine of Hippo (354-430)

Perhaps the best known Christian since the Apostles and Paul. Augustine was a well-known

theologian. In his youth, he had resisted his mother Monica's urgings he become a Christian.

Looking at options, he became a Manichean for a period. After becoming a believer (387AD),

under the influence of Ambrose (337-397) in Milan, he wrote prolifically, opposed heresies and

became a bishop in Hippo, North Africa, in 395. In terms of doctrine, he was close, from the

outset, to the style of the Apostle Paul. Augustine combatted Pelagianism (see separate notes),

insisting that we are all sinners and all need the grace of God for salvation; he (correctly) taught

that the grace of God can be resisted/rejected through individual choice.

Augustine became one of the most important leaders in the evolution of Christianity in the west.

As to the formulation of his ideas, he initially drew heavily on the writings of Plato (however, see

below). His theology focussed attention on original sin and the concept of a "just war". When

Rome fell, he taught that the focus of Christian believes is not on an earthly city, but a City of

God, the Christian community.

August's most famous work was The Confessions, the story of his life and conversion. His On

Christian Doctrine explained how Christianity related to classical learning.

Well known sayings:

| As a young man seeking pleasure: | "Grant me chastity and continence , but not yet".

|

| As a Christian believer: | "You made us for yourself and our hearts find no

peace until they find rest in you."

|

| "What does love look like? It has the hands to help

others. It has the feet to hasten to the poor and

needy. It has eyes to see misery and want. It has the

ears to hear the sighs and sorrows of men. That is

what love looks like."

|

| "I have read in Plato and Cicero sayings that are wise

and very beautiful; but I have never read in either of

them: 'Come unto me all ye that labour and are

heavy laden.' "

|

Some of Augustine's writings were problematic, including his insistence that there is no salvation

outside of the Roman Catholic Church. He also encouraged the use of relics as aids to faith and

taught the existence of purgatory.

John Chrysostom (347-407)

Chrysostom (meaning Golden Mouthed) was at one time Archbishop of Constantinople. He was

well known for his oratory, the stands he took against abuse in the organised church and the

political leadership. A prolific theologian, he wrote more than any of the Eastern Church

fathers. He offended the Empress with his preaching and teaching about the need for

repentance, and was exiled in 403 AD. Roman Catholics know him as the patron saint of orators.

In modern times, proponents of Nazism drew on Chrysostom's anti-Semitism.

Jerome (347-420)

Jerome was the leading Bible scholar and writer in the west during his time. Concerned about

the lack of a reliable translation of the Bible he committed his life to studying the ancient

languages (including, initially, the Greek version of the Old Testament, the Septuagint; he later

based his revisions on Hebrew texts), producing a new version of the Bible (the "Vulgate", for

the "vulgus" or common people) in Latin and writing commentaries on various New Testament

books, including Matthew, Romans and Galatians. He spent much of his life living in Bible lands,

to enable him to speak first-hand about the contexts of texts he was redacting.

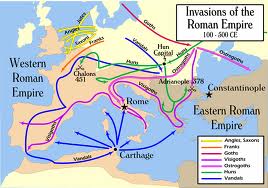

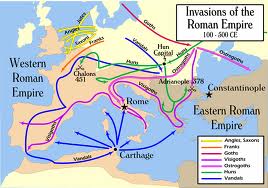

The Visigoths and the Fall of Rome (410, 476)

http://www.google.com.au/search?q=map,+fall+of+rome

Emperor Constantine believed that Rome as a city was too far away from key parts of the empire

and transferred the capital to Constantinople (now Istanbul; built on the foundation of

Byzantium; the city ultimately fell to Ottoman Muslims in 1453).

As a result of this move of the seat of imperial power, the western part of the empire was left

weakened. The Ostrogoths attacked the western empire from the east. The Huns (a tribe from

Asia), attacked from the west. In turn, the Franks, Visigoths and Burgundians overran strategic

parts of the empire. As part of a strategic compromise that further weakened the empire, the

Vandals and Visigoths were allowed to remain within the borders of the empire itself, allegedly

to provide additional protection from the Huns, however this only ensured their continued

encroachment. In 398 AD Alaric (leader of the Visigoths, and an Arian) made further inroads,

eventually capturing and sacking Rome in 410. The Western Roman Empire ended in 476, when

the Germanic general Odoacer deposed the last Emperor Romulus Augustulus.

Additional Reading

A Lion Handbook, 1990, The History of Christianity, Lion

Blainey, G, A Short History of Christianity, Viking, Melbourne, 2011

Freeman, C, AD 381: Heretics, Pagans and the Christian State, Pimlico, London, 2008

Miller, A, Miller's Church History: From the First to the Twentieth Century

Renwick, AM, The Story of the Church, Intervarsity Press, Edinburgh, 1973